Blue Bloods

North American Horseshoe Crabs

Elizabeth Curren

Curated by Judy Southerland

Wednesday, April 26 through Saturday, May 20, 2023

This exhibit is about the life cycle and beauty of the mysterious Horseshoe Crabs that populate the North American coastline from the Yucatan peninsula to southern Canada. Using well beaten flax and watercolor paper, I have created a paper beach, an artist’s book and other components to illustrate the life cycle of these remarkable animals who have populated the oceans for 450 million years.

Two paper Horseshoe Crabs from Under the Full Moon

Click image to enlarge ⦿ Inquire

Under the Full Moon

Elizabeth Curren

2023

Installation measures 90”x 36”

Paper beach: formed from beaten flax; Horseshoe Crabs: watercolors, pencil and crayon on paper; collaged elements.

$2,000

Click image to enlarge ⦿ Inquire

Details from Under the Full Moon

Click image to enlarge ⦿ Inquire

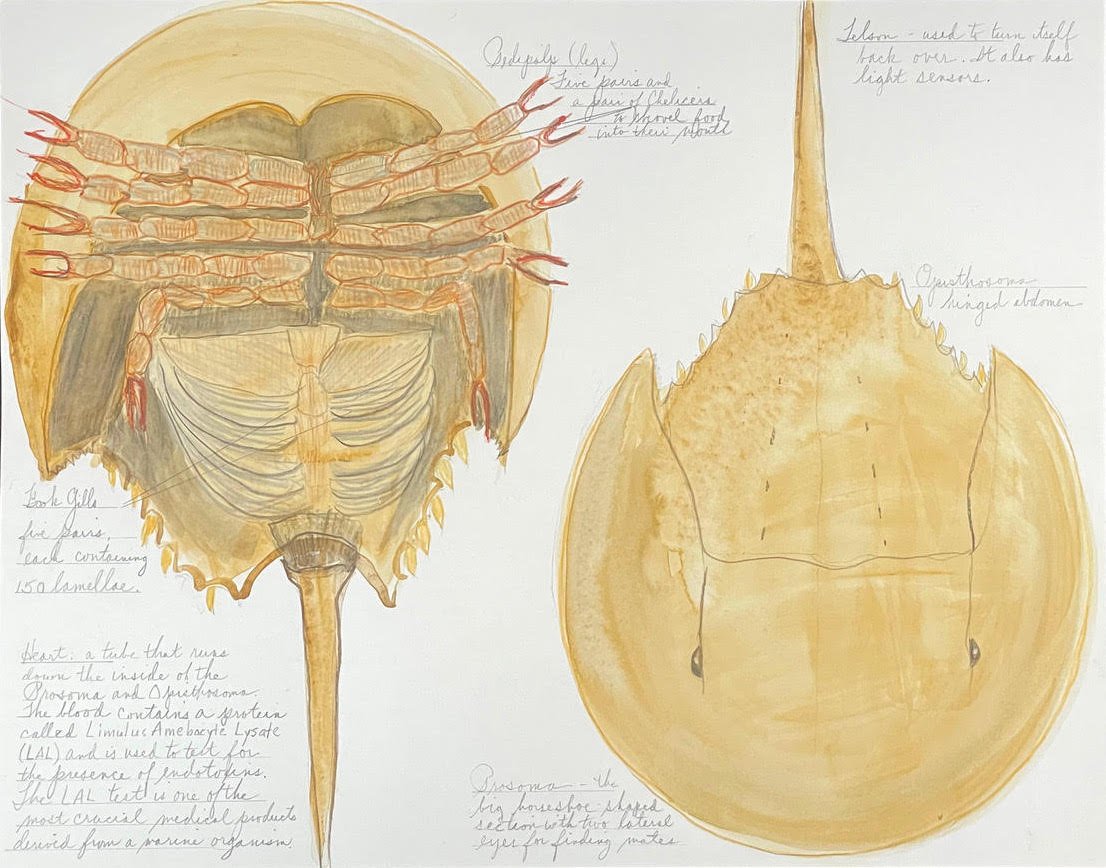

“Female Horseshoe Crabs reach maturity between ten to eleven years of age; they molt at least two more times than males. Females often measure 12” across the prosoma and up to 24” in length, including the tail. Males are smaller and are fully grown at around nine years of age; they develop specially adapted front claws during their last molt which allow them to grasp the rim of the females’ shells during spawning.

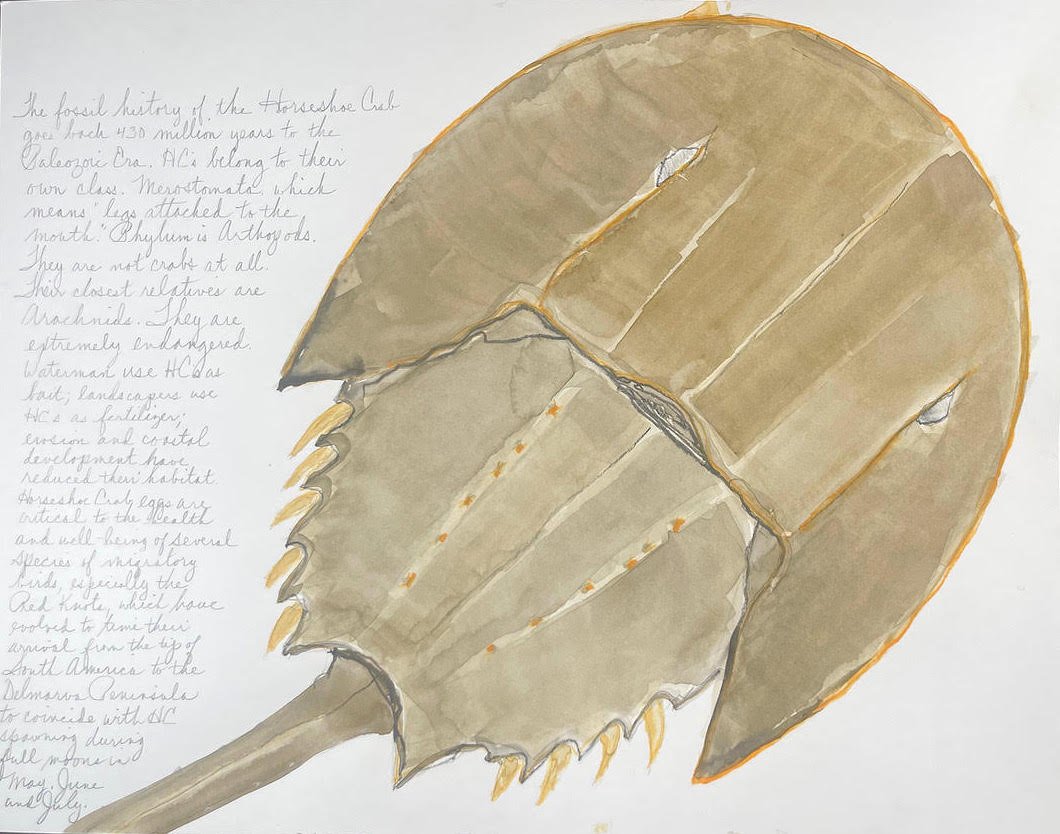

All Horseshoe Crabs have two main eyes which can detect the light of the full moon as well as the presence of other Horseshoe Crabs; they have other sensors along their telsons (tails) which detect UV light. Horseshoe Crab telsons are not weapons; they are used as rudders when swimming and to flip the Horseshoe Crab over when necessary. Horseshoe Crabs have hinged shells: the larger section is the prosoma; the smaller section is the opisthosoma. Underneath their hard shells are the legs and internal organs: heart, gills, mouth, digestive system.

During the mating season, under the full moons of Mya, June, and July, the females search for the largest males in the shallow waters along the East Coast. A female will not leave the water to spawn without a male attached to her back. Smaller ‘satellite’ males often latch on as well. When the female is ready, she will begin the long climb up the beach above the highwater mark of the full moon high tide to where the sand is damp, but not wet, to dig out a nest and lay a clutch of eggs. She will drag the male over the eggs and he will fertilize them. The satellite males will have their opportunity as well. Then they will all head back to the water. The female may return two or three times each night of the days bracketing each full moon, releasing up to 100,000 eggs during the mating season.

Eggs hatch in three to four weeks. Baby Horseshoe Crabs molt several times as they grow. As juveniles, they live in shallow water and consume microorganisms and larvae. Mature Horseshoe Crabs live in up to 200 feet of water and eat sea worms, mollusks, and crustaceans.”

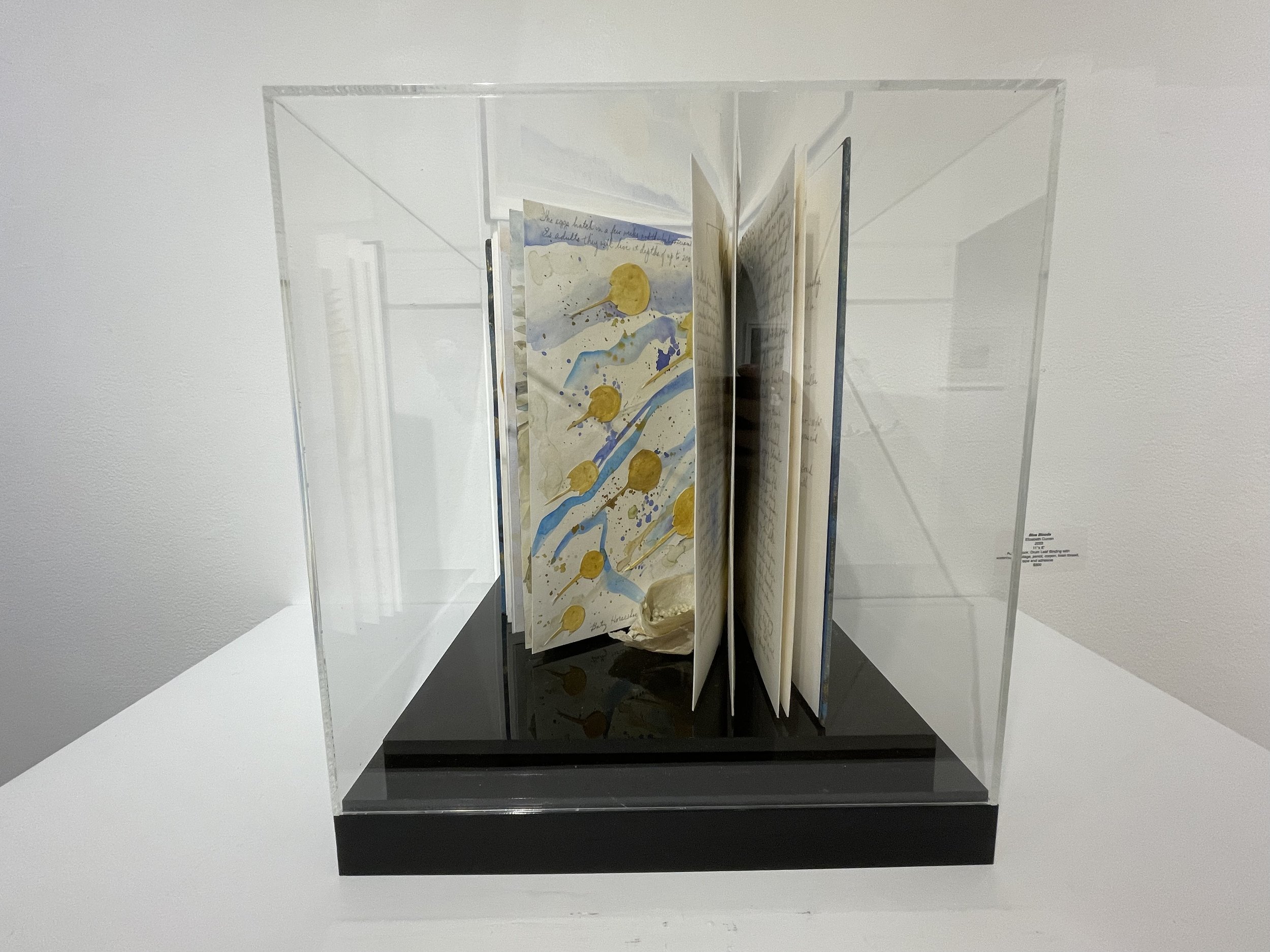

Blue Bloods

Elizabeth Curren

2023

Artist’s Book: Drum Leaf Binding with watercolors, collage, pencil, crayon, linen thread, tape, and adhesive

11’’x 8”

$800

Click image to enlarge ⦿ Inquire

“After spawning, Horseshoe Crabs often get flipped over onto their backs on the beach as the tide goes out. If they cannot right themselves they will not survive in the hot sun. Ten percent die after spawning. Humans can help by turning them over. Never hold them by the tail since doing so can cause grave damage. Always grip the sides of their shells. If possible, carry them to the water and release them in the shallows; often the salt water will revive them.”

In the Shallows

Elizabeth Curren

2023

Installation measures 2’ x 3’

Paper beach: formed from beaten flax; Horseshoe Crabs: watercolors, pencil and crayon on paper; collaged elements

$700

Click image to enlarge ⦿ Inquire

⬆Scan me!

Coming to Shore

Elizabeth Curren

2023

28’ x 22”, framed

Handmade papers and collaged watercolors

$500

Click image to enlarge ⦿ Inquire

Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL)

Elizabeth Curren

2023

Installation with paper Horseshoe Crabs, bottles and liquids

$500

Click image to enlarge ⦿ Inquire

“The fossil records for Horshoe Crabs date back at least 425 to 450 million years; these animals, which are related to spiders and scoprions, predate dinosaurs and most everything else on the planet. Among their unusual features is a protein in the blood which contains a respiratory pigment called hemocyanin; when exposed to air, their blood turns blue.

Horseshoe Crabs do not have an immune system akin to modern animlas. Instead, their blood contains amebocytes which recognize endotoxins, surround them and essentially crush them as the blood coagulates. In the 1960’s, scientists realized that this unique biological defense mechanism could be used to test for bacteria in vaccines and other drugs. They set about developing a method of collecting and processing Horseshoe Crab Blood for medical testing. Limulus Amebocyte Lystate (LAL) is now used worldwide by pharmaceutical companies. LAL is crucial in modern medicine.

Large females are captured, 30% of their blood is removed over about 48 hours, and then they are released. 15 to 30% do not survive the procedure. LAL processing is a big business: a quart is valued at $30,000; $120,000 per gallon. There are five licensed companies in the U.S.

An alternative way to test for endotoxins, called factor C (rFC), was devloped in Asia over twenty years ago; the European Pharmacopeia has accepted rFC as an accepted baterial-toxin test as of 2016, thus paving the way for change in the U.S. However, it has yet to be fully approved by the U.S. FDA and U.S. Pharmacopeia, despite lobbying by U.S. pharamaceutical companies, research studies from NIH and other science facilities, and recommendations from many wildlife and animal rights organizations.

In the past, Horseshoe Crabs have been used by the ton as an inexpensive source of fertilizer; then and now, they have been quartered and used as cheap bait by fisherman; since the 1960’s they have been captured, farmed, and bled for medical science. They are odd and awkward; they are not cute; they have no voice. In their own habitat they are mysterious and beautiful. Horseshoe Crabs have existed longer than nearly any other creatures on earth. Do we really want them to go extinct on our watch?”

Detail of Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL)

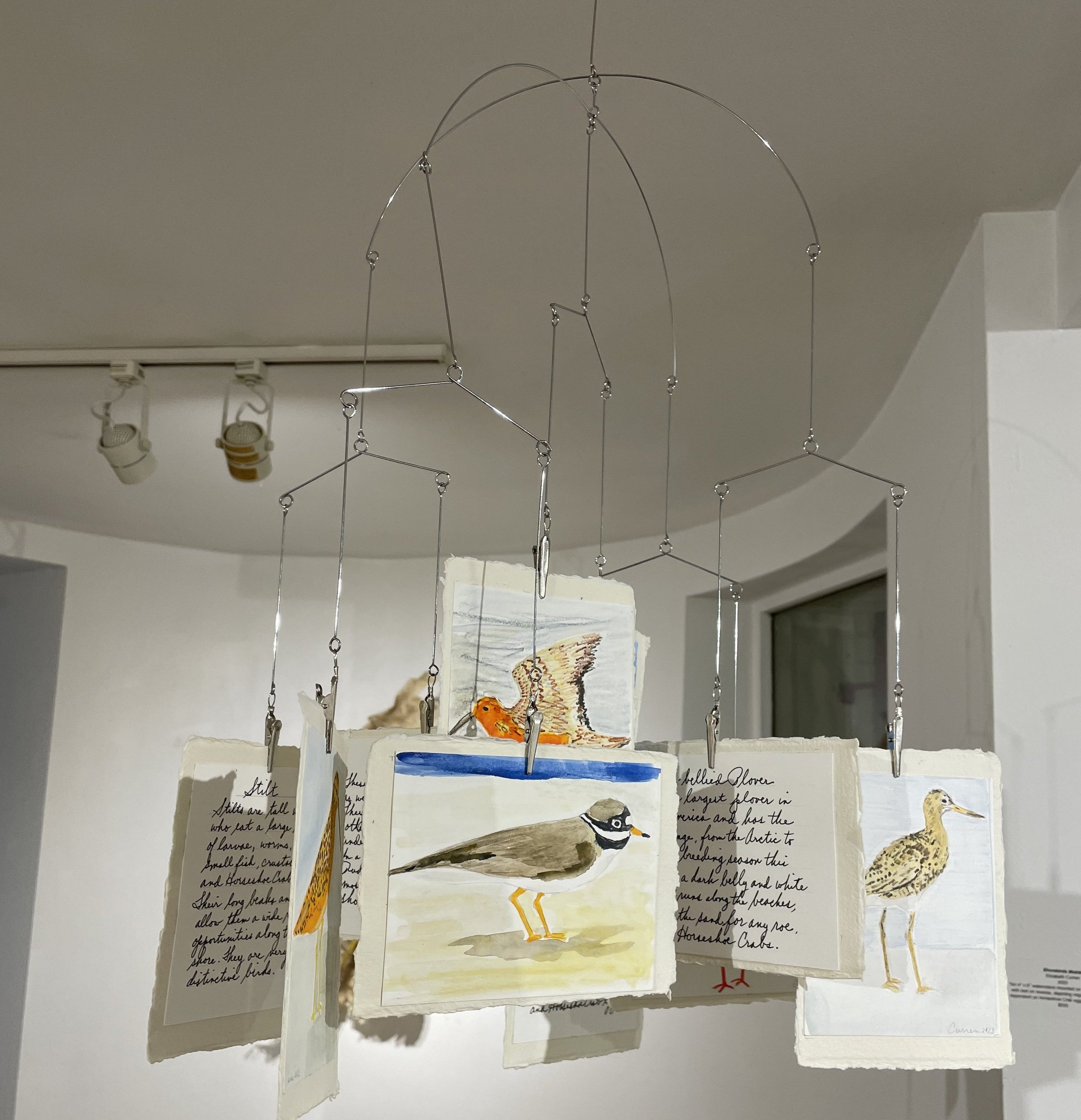

Shorebirds Mobile

Elizabeth Curren

2023

Ten 4” x 6” watercolors mounted on handmade paper with text on reverse, depicting migrating shorebirds dependent on Horseshoe Crab eggs. Metallic mobile

$350

Click image to enlarge ⦿ Inquire

“Horseshoe Crab eggs are the main food source for many species of local and migrating shorebirds, especially the Red Knot. The Red Knot leaves its home in Tierra del Fuego and times its migration to arrive along the mid-Atlantic during the spawning season of the Horseshoe Crab. It loads up on the eggs and then flies to the Arctic to breed and nest. If the Horseshoe Crab egg harvest is poor, the Red Knot flocks cannot produce strong chicks and their young will not survive the migration back to South America. The Red Knots are considered extremely endangered, in large part due to the decreasing numbers of Horseshoe Crabs along the Atlantic coasts.“