“I suspect that it was in this area that the college was unique: one was asked to give something of oneself. It is possible to be lost or suffocated in an institution bent on offering everything, apparently needing nothing.” -Mary Gregory, former Black Mountain College student

Introduction

The Black Mountain College facilities, via their website

What do Elaine de Kooning, Ruth Asawa, and Robert Rauschenberg have in common? Besides being some of the most influential contemporary artists of the 20th century, they all spent time at the small, alternative liberal arts school Black Mountain College. Black Mountain College, located near Asheville, N.C., was a short-lived experiment, only remaining open from 1933-57, but it provided a jumping-off point for many visual artists, writers, and thinkers to learn outside of the boundaries of a formal education. Founded by free-spirited scholar John A. Rice, who rejected the steadfast traditions of academia, Black Mountain College offered a more individualistic education, one that allowed students to participate in experience-based learning and spend time with subjects that lay outside of their areas of expertise. Black Mountain College had no majors, no grades, and no formal lectures. It carried none of the prestige and formalities that draw thousands of students to historic universities each year. And yet it is for that same reason that Black Mountain College is affiliated with some of the most famous artists of the age. The community was almost entirely self-selected, with established artists, writers, and philosophers invited to share what they loved, and students fully committing themselves to the collective work done in the classroom. This small, passionate community of learners shaped the lives and careers of everyone who passed through it, and can be accredited with inspiring some of the most innovative work of the 20th century.

After John A. Rice was asked to resign from a third university for his controversial attitude towards higher education, he decided to establish his own college that reflected his values. Rice rented a few buildings 20 minutes outside of Asheville, and got to work recruiting faculty members, many of whom had just resigned from his previous university in support. Notably, Rice enlisted Josef and Annie Albers, German Bauhaus artists fleeing the Nazi regime, who employed Bauhaus philosophy to establish an alternative methodology for the college. Rice founded Black Mountain College on the values of experiential learning, open dialogue between students and faculty, and a foundational knowledge of art. Most importantly, he wanted his institution to exist outside of the authority of trustees and administration, so the college was owned and operated completely by faculty members, with assistance from students (this, unfortunately, has a lot to do with why the college closed in 1957 after running out of money, but the sentiment was profound).

The college was founded in a former YMCA summer camp building, then eventually relocated to a permanent location. True to its summer camp roots, many aspects of life at Black Mountain College were completely communal. Students and faculty helped with campus maintenance, which included tending to a community farm. Decisions surrounding the university’s policies were established by committees of both students and faculty, and the college’s landscape changed from year to year due to the shifting philosophies of its members. This collective decision-making even resulted in the call for resignation of the college’s founder, John A. Rice, in 1940. After 25 years of exploration, conflict, and change, funds started to dwindle, and Black Mountain College was forced to dissolve. However, the space is commemorated by the Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center, located in downtown Asheville, which celebrates the intellectual and artistic legacy created there.

Informational page on the college’s work program, from BMC’s online collection of works

Summer Sessions

As the philosophy of the college was fluid, so was the student body; Rice encouraged many artists and teachers to visit and spend as much time as they wanted teaching and creating, and Josef Albers continued with this tradition after Rice resigned. Black Mountain College is now known for its historic summer sessions, which started in 1944 as a response to the hardships of World War II. Albers invited contemporary artists to learn and teach at the college, many of whom went on to have prolific careers, but were virtually unknown when they arrived on campus Those summers now mark seminal transitions in many artistic careers of the 20th century.

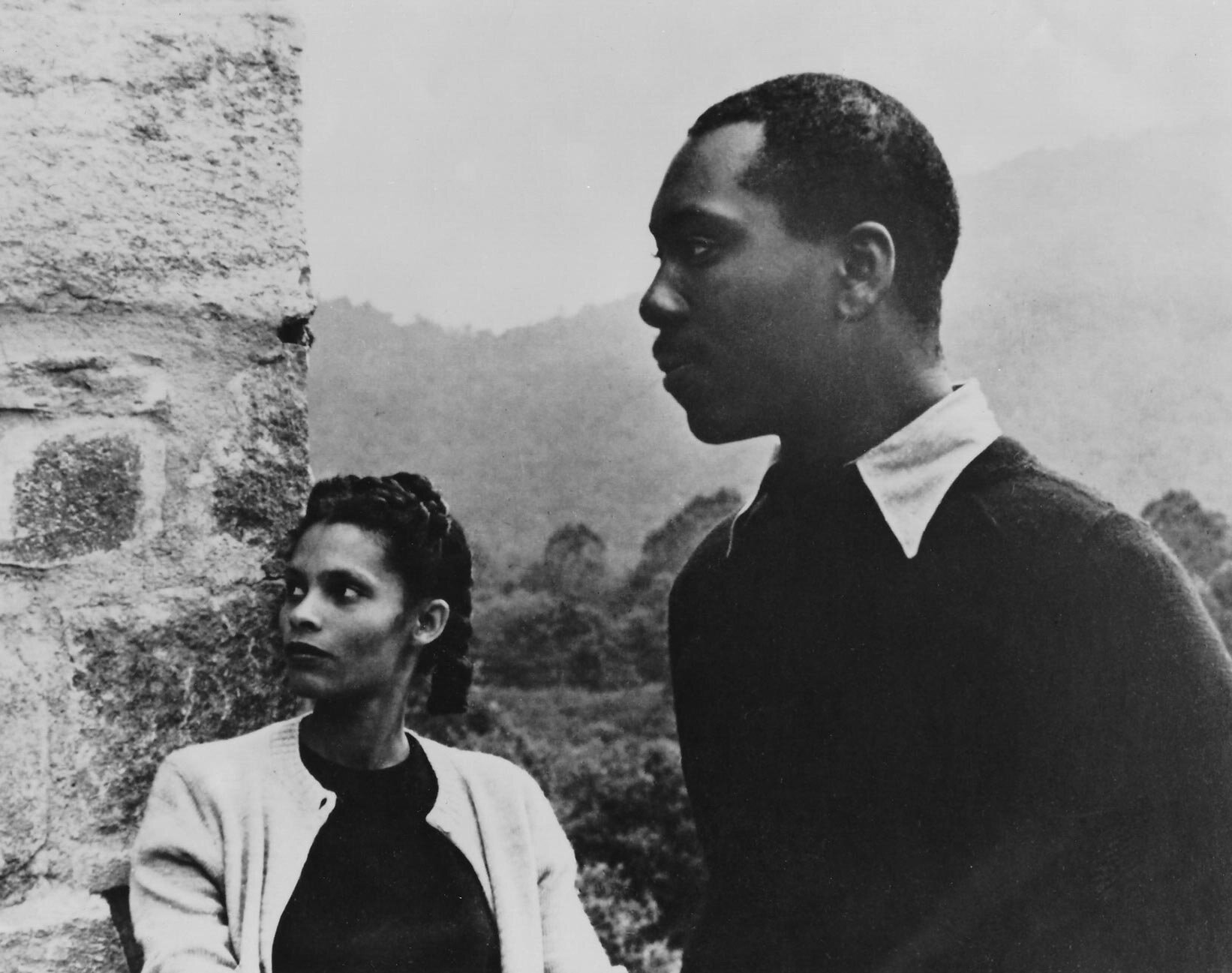

Photo by Nancy Newhall of Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence, Black Mountain College, 1946, via BMC’s digital resources

For example, Jacob Lawrence spent the summer of 1946 teaching at Black Mountain College, upon Albers’ request, where he derived inspiration from Albers’ teaching methodology, which emphasized the importance of “learning to see” within art education. In a 1968 interview, Lawrence spoke of his experience teaching at the college, remarking, “Teaching has been a very good thing for me. It's led me into areas of exploration, areas of thinking which I may not have gone into had I not had the experience of teaching. When you teach, it stimulates you. You're forced to formalize your own theories so that you may communicate them to students.” Lawrence’s time at Black Mountain College was commemorated by a 2018 exhibition at the site’s museum.

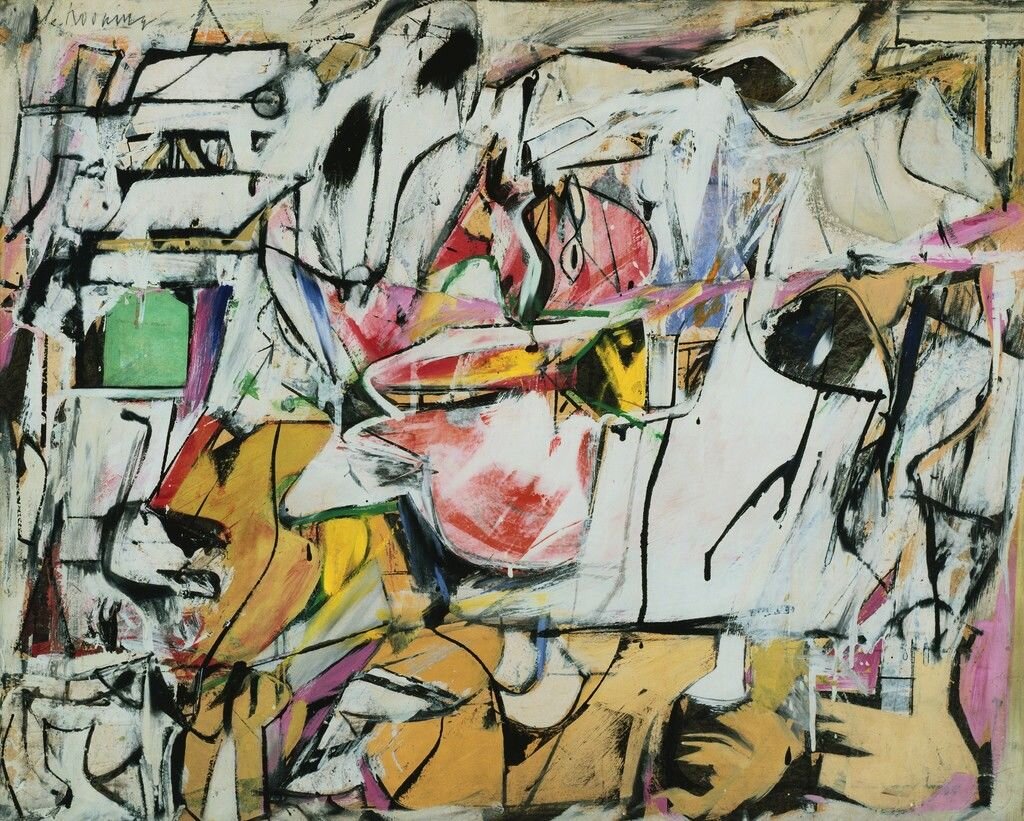

Willem de Kooning, Asheville, 1948. Oil and enamel on cardboard. 25 9/16 x 31 7/8 in. The Phillips Collection. Photo via blackmountaincollege.org

In 1948, Albers invited Elaine and Willem de Kooning, now-renowned members of New York City’s contemporary art scene who were penniless at the time, to Black Mountain College for the summer. Willem taught painting and Elaine learned from the other artists working on campus. That summer, Elaine studied with Albers, as well as architect/inventor Buckminster Fuller and dancer/choreographer Merce Cunningham. Though the pastoral environment and communal lifestyle brought the couple out of their comfort zone, both returned to New York in the fall with works that transformed their careers: Willem, though he claimed to not have enjoyed the summer, created the seminal painting Asheville during his secluded studio time at the college, which marked a breakthrough in his experiments with ‘collage painting.’ Elaine de Kooning immersed herself in campus life and participated in many collaborations with artists like Fuller and Rauschenberg. Her interdisciplinary explorations through performance, and architecture yielded a 16- painting series of “Black Mountain Abstractions,” which sparked an exploration into abstraction that would elevate her career. de Kooning stayed behind in Black Mountain after her husband returned to New York City, and she continued to cultivate valuable relationships with her contemporaries. Indeed, as a product of her newfound inspiration and friendships, four years later, Elaine celebrated her first solo exhibition.

Black Mountain College and Craft Art

Anni Albers, Red Meander, 1954, via The Josef & Anni Albers Foundation

Ruth Asawa, Untitled, 1955, Whitney Museum of American Art

I first came across Black Mountain College in the context of the Whitney Museum of American Art’s latest exhibition, Making Knowing: Craft in Art, 1950–2019. I was struck by the amount of artists I came across in that exhibition whose bios included involvement in Black Mountain College. In a gallery description for the exhibition, the Whitney Museum cites Anni Albers’ presence at BMC as a driving force for craft art in the contemporary scene. And indeed, Albers’ contribution to the curriculum at Black Mountain College encouraged young craft artists of all backgrounds to experiment with alternative materials and step outside the realm of painting and drawing. Albers was a weaver, a role she was assigned to as a woman in the Bauhaus sphere, but one that she turned into a revolutionary contemporary practice at Black Mountain College. Albers infused traditional weaving practices with the fluid abstraction of the Bauhaus movement, creating work that was new and free, and encouraged her students to explore alongside her. Albers set up a weaving workshop on campus, and welcomed students to experiment with all sorts of craft practices, including ceramics, textiles, and jewelry. Creators like Ruth Asawa, whose intricate metal-woven sculptures hang in many major contemporary art museums, and Karen Karnes, whose pioneering ceramic techniques made her “a major icon in American craft,” profited off of the college’s emphasis on artistic exploration through alternative materials. Black Mountain College’s commitment to craft helped bring artists to the forefront of the fine arts world who might have been left behind had they chosen a more traditional education. Craft art, with its ties to feminine domesticity and indigenous practices, is often overlooked by museums and galleries who prefer the traditions of the Western canon, and often spurn minority artists for that same reason. However, as more and more craft art exhibitions pop up everyday, it is clear that contemporary craft art belongs in the art world, as do the distinct voices of craft artists. It is clear that the community at Black Mountain College had that understanding ahead of its time, and helped to kickstart contemporary craft art’s exciting transition to gallery and museum spaces.

Ruth Asawa and Alma Stone Williams by unknown photographer, Black Mountain College, 1946, via BMC’s digital resources

The Philosophy of Black Mountain College

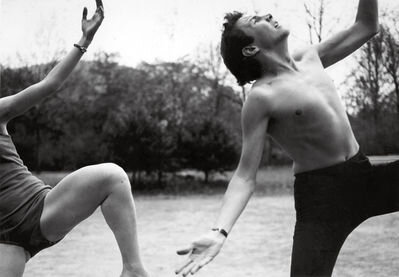

Hazel Larsen Archer, Elizabeth Schmitt Jennerjahn and Robert Rauschenberg, c. 1952, via artsy.net

There is much to learn from the philosophy of Black Mountain College. The college fostered a self-selecting, self-motivated community, which drove the strength of its ideals. Artists and thinkers gravitated towards the college, hoping to add to the ongoing conversations taking place on campus. With the absence of grades and passive lectures, students were instead encouraged to become active participants in their learning, pushed to learn from experience and measure success by the process rather than the result. Founder John A. Rice was known to state, “To know is not enough; it’s what you do with what you know that is the important thing.” This thinking applied to the communal living of Black Mountain College: students would use their skills to enrich their surroundings, whether that meant renovating a building as part of an architecture course, or experimenting in the garden during a biology course. Physical labor was widely incorporated into the lifestyle at Black Mountain College; to foster a life independent from trustees and administrators, it was necessary for all members to work to keep the school running. Students were encouraged to collaborate with each other across disciplines, working together to enrich their learning process as well as their surrounding community. There were no limits to what students could pursue, which resulted in an interdisciplinary education that fostered a holistic understanding of themselves and their paths. Outside of the classroom Black Mountain College had a vibrant on-campus life, driven by collaborations between faculty and students, which included performances, lecture series from prominent visiting speakers, and collaborative projects and conversations.

Hazel Larsen Archer, Buckminster Fuller inside His Geodesic Dome, 1949, via artsy.net

When reflecting on the practices of Black Mountain College, it is clear that the profound success of its alumni cannot only be measured by more superficial accomplishments, although the sheer amount of alumni who went on to achieve some level of fame and fortune is telling. More so, reading the testimonies of former students and researching how the school’s philosophy informed the artistic practices of its students exemplifies the profound impact of the self-made artistic community. The college was a place driven by learning and creation, but it was less of a one-sided conversation than an ongoing discussion between all involved. Students went on to become faculty, faculty members studied from students, and everyone who came across the college contributed to the constant flow of creative collaboration taking place there. Black Mountain College started as an experiment and ended as a movement; one that was not logistically sustainable, but metaphorically significant long after campus doors closed. Now, the Black Mountain College and Art Center upholds the institution’s legacy, as well as their extensive library of records. Institutions like Studio Gallery also uphold the legacy of Black Mountain College in being an artist-run, collaborative institution, fostering creativity through conversation and community participation.

For more information, feel free to explore the following sources:

This is a longer list of notable alumni and visiting artists, but it is not comprehensive:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Black_Mountain_College_alumni

From Staff Contributor Thea Hurwitz