“I keep painting until there is nothing more to say.”

——Jennie Lea Knight, in conversation with Claire List for the Corcoran Gallery of Art’s retrospective Images of the 70s: 9 Washington Artists

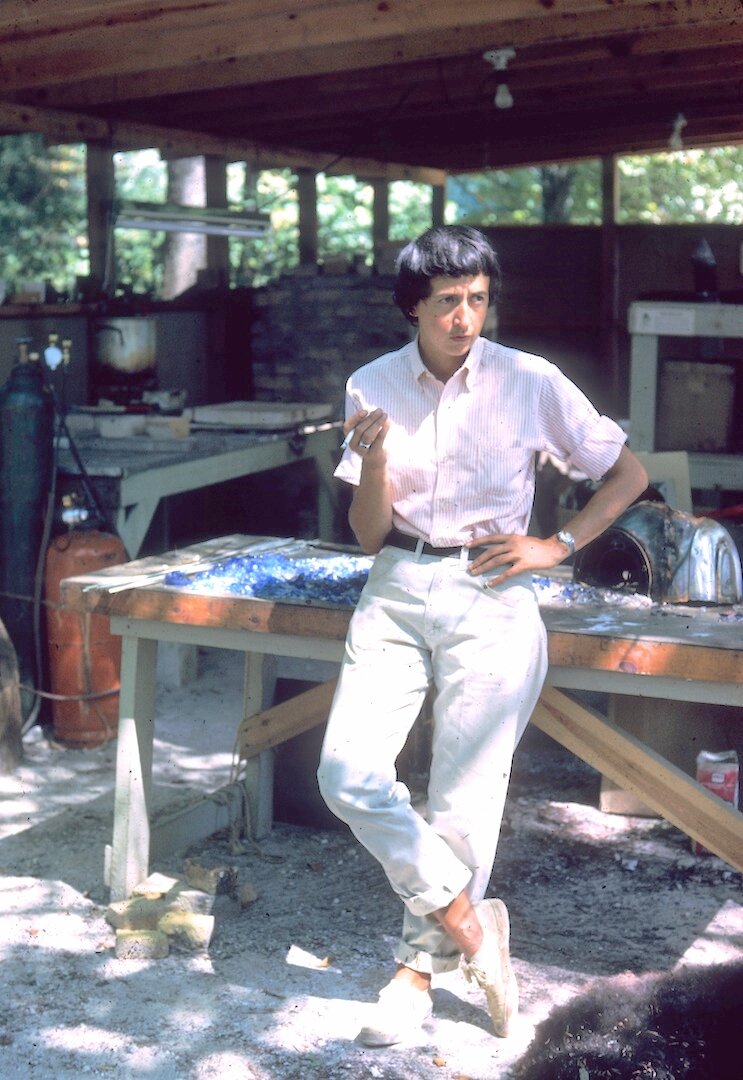

Imaged sourced from Studio Gallery’s Photo Archive of Jennie Lea Knight

This month at Studio Gallery we commemorate our founder, Jennie Lea Knight, through an exhibition celebrating her life and work. Knight was a sculptor and painter whose work focused primarily on the natural world. Her art is featured in the collections of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Phillips Collection, the National Museum of Women in the Arts, and many other prestigious art institutions, and she is considered a seminal figure in the D.C. art scene. Her foundation of Studio Gallery was a trailblazing move for a woman artist, and made space for a diverse, multi-generational community of artists.

Jennie Lea Knight, Wing, Bronze, 8 1/2" x 6" x 15,” photo sourced from an online archive of Knight’s work compiled by Kathryn Scott

Early Life:

Jennie Lea Knight was born March 31, 1933, in Washington, D.C., and died March 23, 2007, in Haymarket, VA. She spent part of her childhood on a farm in southern Maryland, where she experimented with painting and loved to collect animals (Corcoran). Knight was homeschooled until she was 15, where she tried to enter high school, but disliked it, then went on to study at the King-Smith School of Creative Arts. Knight herself described the King-Smith School as a ‘finishing school’ that prioritized art education for young women. Eventually the art faculty moved buildings and formed the Institute of Contemporary Art by the time she graduated. Knight started out studying design and music, but ended up gravitating towards painting, ceramics, and later sculpture. The ICA followed the teachings of the Washington Color School very closely, which was an abstract expressionist art movement that prioritized vibrant color and simplicity. According to the Archive of American Art, “The school's philosophy was based on Sir Herbert Read's Education Through Art and provided professional training in painting, sculpture, literature, music, and theater. In addition, the ICA operated an evening school and brought prominent artists and literary figures to the nation's capital for exhibitions, concerts, workshops, lectures, readings, and performances. Teachers at the school included potter Alexander Giampietro, sculptor David Aaron, designers Beatrice Takeuchi and Hubert Leckie, and painter Kenneth Noland.” Read’s philosophy dictated that “. . . art should be the basis of education.... The aim of education is the creation of artists - of people efficient in the various modes of express (Keel 47).” Knight was encouraged to explore the world around her through art by esteemed instructors such as Kenneth Noland, a Black Mountain College alum who later became an instructor at the ICA. He is considered a “defining Color Field painter.” Studying at the ICA was a unique opportunity to receive such a sophisticated art education as a young woman in the 1950s, but the rigidity of the curriculum did not gel with Jennie Lea Knight’s free spirit. A self-proclaimed “visual person,” Knight decided that “I came away from the Institute with little formulas for how to make a painting, but that really had nothing to do with me as a person (Corcoran).”

Jennie Lea Knight, Abstract-tube with wood, on wood & clay, Clay (red & tan), oak, 25" x 5 1/2" x 9" 1978- photo sourced from Kathryn Scott’s online archive of Knight’s work

Jennie Lea Knight as a child, photo sourced from Studio Gallery’s photo archive

After being surrounded by such a rich artistic community, perhaps Knight was inspired to incorporate the model of the arts collective into her professional life. She graduated from the ICA in 1951, then went on to receive undergraduate and graduate degrees from American University. There, she primarily studied under Robert Gates, James Caudle, and William Calfee. Robert Gates was the head of the AU art department at the time Knight studied there. He was a loose, vibrant painter who focused primarily on the natural world, which may have enforced Knight’s commitment to drawing from the natural world to form her body of work. Caudle was a sculptor who ended up sharing a studio with another one of Knight’s mentors, Kenneth Noland. He was esteemed for using a difficult lead sculpture technique, and worked primarily in the abstract. His works undoubtedly inspired Knight to experiment with various metals and natural materials, including bronze casting, which she studied later on at the Penland School of Crafts. William Calfee definitely enabled Knight’s experimentation with bronze; he was a prolific large-scale sculptor that helped establish the fine arts department at American University. He encouraged experimentation, and his works were largely abstract. Jennie Lea Knight received a sophisticated traditional art education, but her commitment to sculpture was primarily individualistic: she was never able to take sculpture classes at American University, so she had to go explore those skills herself. In fact, she says gravitated towards sculpture not primarily because of her prestigious mentors but because her first forays into whittling “felt very good,” exemplifying her personal relationship with the process (Corcoran). As a woman creating sculpture in a largely male-dominated art world (particularly for three-dimensional work), she combined her influences and her own personal artistic values to forge a path for herself with bold, thoughtful artworks.

Early Career:

"Sculpture will always be my most comfortable media," Knight said in a 2002 essay for the Jane Haslem Gallery. "I think like a sculptor. I like the tangible quality of sculpture. It is something that you can touch. It is not elusive. The basic [tenets] of sculpture are simple, dealing with the same problems that we have to deal with in our own bodies, balance, strength, weight, posture, size, and space. Sculpture is not an immediate process. It takes time. . . “

Knight pictured at Penland School of Crafts, photo sourced from Studio Gallery’s archive

After her time at American University in 1964, Knight began to find her voice as a sculptor when she spent two summers fine-tuning the ‘lost wax’ method at the Penland School of Craft, a woman-founded craft school that welcomed students from all walks to life to hone their craft practices. Lost-wax casting is an ancient practice that requires the artist to create a negative space wax mold to pour bronze around. The wax then melts in the firing process, leaving behind a hollow, high detailed sculpture. It is a labor-intensive technique that requires a lot of skill and prior knowledge, and for Knight to be working within such a traditionally male practice at such a difficult time for women artists speaks to her fortitude and artistic prowess. The year after, she studied at the prestigious Fonderia Battaglia in Milan, a historic bronze casting foundry that has employed lost-wax casting techniques since 1913. During this time Knight also became an instructor, teaching at various day schools around the DMV, as well as prestigious institutions like the Corcoran School of Art and Design, the Art League School and George Mason University.

An interesting feature of her career aside from founding Studio Gallery is her stint as a photographer and illustrator for the National Institute of Health. According to her obituary from the Washington Post, one of her most distinctive projects at NIH was ‘an atlas of the monkey brain.’ Her time at NIH speaks to her other great scholarly interest and love: animals and wildlife rehabilitation. She focused on scientific drawings of animals, and even assisted in animal studies. She had previously worked as a veterinarian's assistant, so this job combined her scientific and artistic interests perfectly. An article from the NIH about Knight states that “Jennie, who has been a serious artist all her life, has been able to combine her artistic talents with her knowledge and interest in animal physiology. Her main work in the lab is to provide all the illustrations the section requires. This ranges from graphs and charts through on the-spot surgical drawings to photographs and illustrations for journal publications (NIH Records 3.14.1959).” Knight also worked directly in the lab setting. She trained monkeys for experiments, and prepped equipment for surgical research.

Studio Gallery:

Despite her successes, Knight always felt frustrated at the fact that, despite her talents, she was ultimately kept out of the art world as a woman artist. She decided to carve out a space for herself, and by doing so enabled the careers of many marginalized artists after her.

Excerpt from an NIH employee feature on Jennie Lea Knight, image sourced from the NIH archives

Jennie Lea Knight founded Studio Gallery in 1956 with her mother, Vera Knight, and her sister, Nancy Floyd, in their family home in Oldtown, Alexandria. The space was one of the first professional galleries in Northern Virginia, and undoubtedly a landmark institution due to it being founded and run entirely by women. The three women worked together to run every aspect of the gallery from top to bottom; showcasing their own work and eventually extending their reach to the surrounding community. Studio Gallery became both a haven and a jumping-off point for marginalized artists from the DMV and, eventually, around the country. Though the gallery did not start off as an art collective, the institution’s values of collaboration and diversity drew together a community of working artists who were able to share professional and personal resources with one another. Throughout art history, some of the most influential art and social movements have stemmed from community initiatives; from artists coming together to advocate for one other and stand against the status quo. Knight was able to effectively use her privileges and talents to change the landscape of her community, and of the art world in general. Her focus on community was exemplified by her choice to turn Studio Gallery over to its artists in 1964, officially establishing the space as an artists’ collective.

Knight at a 1962 Studio Gallery Exhibition, photo sourced from Studio Gallery’s photo archive

Personal Life:

Studio Gallery’s foundation was intertwined with Jennie Lea Knight’s family life; she worked with her mother and sister on the upkeep of the gallery and ended up giving up ownership when her parents passed away. Another important person in Knight’s life was her partner, Marcia Newell. At the time of Knight’s death they had been together for 40 years, and enjoyed much of their time together on their farm in Haymarket.

Knight’s Body of Work:

According to Knight’s obituary in the Washington Post, “She lived on a working farm in Haymarket, where, while wielding chainsaw and chisel, she was inspired by natural lines and shapes as she tended animals and cut hay from the rolling hills.”

Knight’s body of work is inextricably linked with nature. She lived on a farm in Haymarket, VA, for much of her artistic career, and worked in wildlife rehabilitation in conjunction with working on her sculptures. This connection with the natural world is evident in her work: Washington Post art critic Paul Richard noted “...a warmth, a subtlety, a set of evocations of ponds and gentle hills and curving biomorphic forms. The wood she uses no longer seems a kind of substitute for Tony Caro's metal or Noguchi's stone. It has been used as directly and as lovingly as a farmer uses land. . . . They do not look theoretical, invented. They look as if they've grown." Indeed, Knight’s wood sculptures seem grounded in nature; though their forms remain ambiguous, they are ultimately familiar. Knight employed both subtle curves and unexpected lines to create her sophisticated wood sculptures. Knight’s drawings and paintings also respond to the natural world, from the subtly rendered ‘Emily Sleeping,’ a lithograph of a dozing cow, to the layered and evocative graphite drawing ‘Creek Willow.’ Paintings like ‘Bluescape’ (1970) speak to a practiced knowledge of color theory, coupled with her observations of the color combinations in the environment around her.

Knight pictured with her partner, Marcia, photo sourced from Studio Gallery’s archive

Later on in her career Knight turned back to painting in order to chase after the “intensity” of the animals she wanted to capture (Corcoran). However, these works were not nearly as well-received as her sculptures, forcing Knight to reconcile with the boundaries of the art world once again and affirm herself as a woman artist creating exactly what she wanted to create.

“The element I found really exciting was what happened inside the shape itself, not what was going on around it.” (Corcoran)

Knight’s works from a 2020 show at Cody Gallery in Marymount University

Working both from life and from the abstract, Knight’s work emphasizes line and energy, whether she was manipulating charcoal and acrylic or using a chainsaw to carve out a large-scale wooden sculpture. The amount of works she created that were inspired by life on the farm emphasize the joy she found in her home and in nature. Knight seemed to view her works as an investigation into nature; when asked if she valued process over product, she responded: “Yes, the process is the most valuable aspect of the experience. I start out with a hypothesis, and I wonder if it is possible. The only way that I can prove it is by producing a piece of sculpture (Corcoran).” Once again, Knight appears to infuse her artwork with a scientific curiosity.

Late Career:

Late in her life Knight became afflicted with fibromyalgia, and later developed cancer as well. Due to her illnesses’ debilitating effects on her range of motion, she committed herself to continuing to make work, but at a much smaller scale. She started working on very small sculptures, primarily of animals living around her farm. This resulted in a body of work that still reflected her energy and love for the natural world, just in miniature. Her last art show was in 2004 at AU’s Watkin’s Gallery, where Knight talked about her processing how to move forward:

"Initially I couldn't think of what I was going to do with myself," Knight said. "It was just plain painful work with the heavy machinery [required to create the large sculptures]. I knew I couldn't just sit there and watch television all day. I had to do something. Then I stopped thinking about what I couldn't do, but what I could do."

Jennie Lea Knight, Emily - goat, Oil on linen,26 ¾” x 20 ¾”, signed, 1979, photo sourced from Kathryn Scott’s online archive

Jennie Lea Knight, Self portrait - young, Oil on canvas, 15” x 21,” date unknown, photo sourced from Kathryn Scott’s online archive

Conclusion:

Jennie Lea Knight, Owl, Bronze on red marble base, 3 1/2" x 2 7/8" x 3 1/4", unsigned, no date- one of her smaller works

Jennie Lea Knight was an eclectic and remarkable artist and community member; someone who capitalized on rare opportunities and turned them into institutional practices that benefited her community and many artists to come. Despite the boundaries that kept women and LGBTQ+ individuals out of the mainstream art world, Knight was able to earn a sophisticated art education and forge a path in a largely male-dominated medium within an already patriarchal field. The image of her, as a young queer woman, wielding a chainsaw to carve out her large-scale wooden sculptures, exemplifies her fortitude and individuality. That individuality is inherent in her body of work; she neither conforms to gender roles or outright rejects them, as she embraced the more traditionally masculine mediums of bronze and wood while also continuing to expand upon her pastoral drawings and paintings. All her works play off one another in their fluidity, energy, and interaction with their environment. Knight did not compromise on any aspect of her inquisitive nature; she effectively combined her interests in art and animal physiology in her job at NIH, her time as a veterinarian’s assistant, and her continued commitment to wildlife rehabilitation at her farm up until the end of her life. To Knight, there was no need to separate the disciplines of art and science, or differentiate between the boundaries of the studio, the laboratory, or the outside world. Jennie Lea Knight forged a lasting connection between her individual art practice and her surrounding community, establishing Studio Gallery as a space for self-advocacy that would expand far beyond her reach and become a fixture in the DC area. Her generosity is a common thread throughout her life’s story, whether that presents itself in her care for animals, concern for marginalized artists, or commitment to serving her community.

For more images, please refer to Kathryn Scott’s extensive online archive of Knight’s works:

As well as Studio Gallery’s Photo Archive

References:

Images of the 70s: 9 Washington Artists, Corcoran Gallery of Art, January 18-March 16, 1980, Washington, D.C.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/04/08/AR2007040801115.html

https://americanart.si.edu/artist/jennie-lea-knight-2670

https://www.studiogallerydc.com/ourfounder

https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/institute-contemporary-arts-records-9688

https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/artist/Kenneth-Noland

https://www.zhibit.org/profile/jlknight

https://nihrecord.nih.gov/sites/recordNIH/files/pdf/1959/NIH-Record-1959-04-13.pdf

https://www.american.edu/cas/museum/2020/robert-franklin-gates-paint-what-you-see.cfm

http://williamhcalfee.org/about-william.php

https://italia-sumisura.it/en/azienda/fonderia-artistica-battaglia/

Keel, J. (1969). Herbert Read on Education through Art. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 3(4), 47-58. doi:10.2307/3331429

https://www.fonderiabattaglia.com/index.php?node=static&static=fusione-cera-persa

https://wikivisually.com/wiki/Jennie_Lea_Knight

https://nihrecord.nih.gov/sites/recordNIH/files/pdf/1959/NIH-Record-1959-04-13.pdf

https://www.theeagleonline.com/article/2004/09/watkins-exhibit-features-au-alum

https://www.theartstory.org/movement/washington-color-school/

From Staff Contributor Thea Hurwitz