Photo courtesy of pinterest.com

When you were a child, what did you know about art? You were probably walked around museums at a certain point, had famous works pointed out to you on TV or in books, and were encouraged to paint, draw, or play with clay. These were all deliberate attempts to give you an understanding of art and your ability to create. But you were also probably read to, which means you were saturated with colorful images of rainbow fish, mischievous monkeys, and soaring castles from infancy. These images swam in your mind, excited your imagination, inspired you to dream, look, and create. Children’s books are used as a tool for language acquisition and literacy, and are a staple of any family home. But what about their role in promoting visual understanding? What purpose do they serve in the art world? The line between illustration and fine art seems impossible to cross at times, and children’s literature is usually confined to its own category. However, in actuality visual art education and literacy education are intrinsically linked. When I close my eyes and picture the great green room in Margaret Wise Brown’s Goodnight Moon, I am immersed in the scene and overcome with visceral emotion, just like when viewing works like Monet’s Water Lilies or Van Gogh’s Starry Night. The imagery of children’s books has become ingrained in cultural memories and welcomed into family traditions across the world. Children’s literature occupies an essential niche in the art world, as the sustained impact of a picture book can access individuals at all stages of life. Picture books can also represent the essential artistic relationship between the word and the image; the dynamic between text and illustration is a common tool for children’s book authors. However, some authors display effective storytelling solely through imagery. Many famous children’s book authors, like Maurice Sendak, Eric Carle, and Clement Hurd, came from professional illustration and design backgrounds, and used their knowledge of visual arts to propel their engaging stories.

As Peggy Albers states in her article “Theorizing Visual Representation in Children’s Literature”, “...children often see their world and begin to recognize patterns before they learn oral and/or written language. They begin their understanding of the world through looking and seeing. How they look and see, however, are often situated in the way children’s literature artists look at and see their world through the images they render (Albers 165).” Since the image reaches children at the earliest stages of development, it is safe to say that visual language is integral to our understanding of the world and ourselves. Therefore, artistic style, motifs, and intentions play a huge role in conveying a story’s themes to the reader. Perceiving children’s books as art objects as well as works of literature opens up the art world to a host of fantastic works that have impacted how we see the world.

In her article “Sendak’s Sustainable Art,” Amy Sonheim proposes that the following misconceptions keep children’s literature from becoming integrated into the art world: “Texts for children are less thoughtful because children are less intelligent. Art for children is less fine because children are less observant. Illustrations for children reiterate texts and decorate pages, playing negligible roles in the storytelling. If a book is short, it is simple (Sonheim 116).” In discussing the role of children’s literature in fine arts, it is common to try and convince adults that picture books are ‘not just for kids’ in order to convey the legitimacy of the genre. However, I don’t see this distinction as completely necessary. Some picture books are, indeed, solely intended for children, and most children’s books are created with child development in mind. This does not make them less artistic, nor is there somehow less thought put into their creation. It is possible to reconcile the developmental impact visual storytelling can have on children while also understanding its cultural impact and appreciating the beauty, drama, and compassion present in the genre. The following authors of some of the world’s most impactful children’s books are all true artists at heart. None of them identify solely as children’s authors, perceiving their picture books as a part of their larger artistic practice. Their books defy the misconceptions proposed by Sonheim; they are profound and expertly rendered, with boundless illustrations that drive the story. The stunning visual artistry of these books has played an essential role in the development of countless children, and has also had a defining impact on the art world.

Maurice Sendak (1928-2012)

Photo courtesy of bustle.com

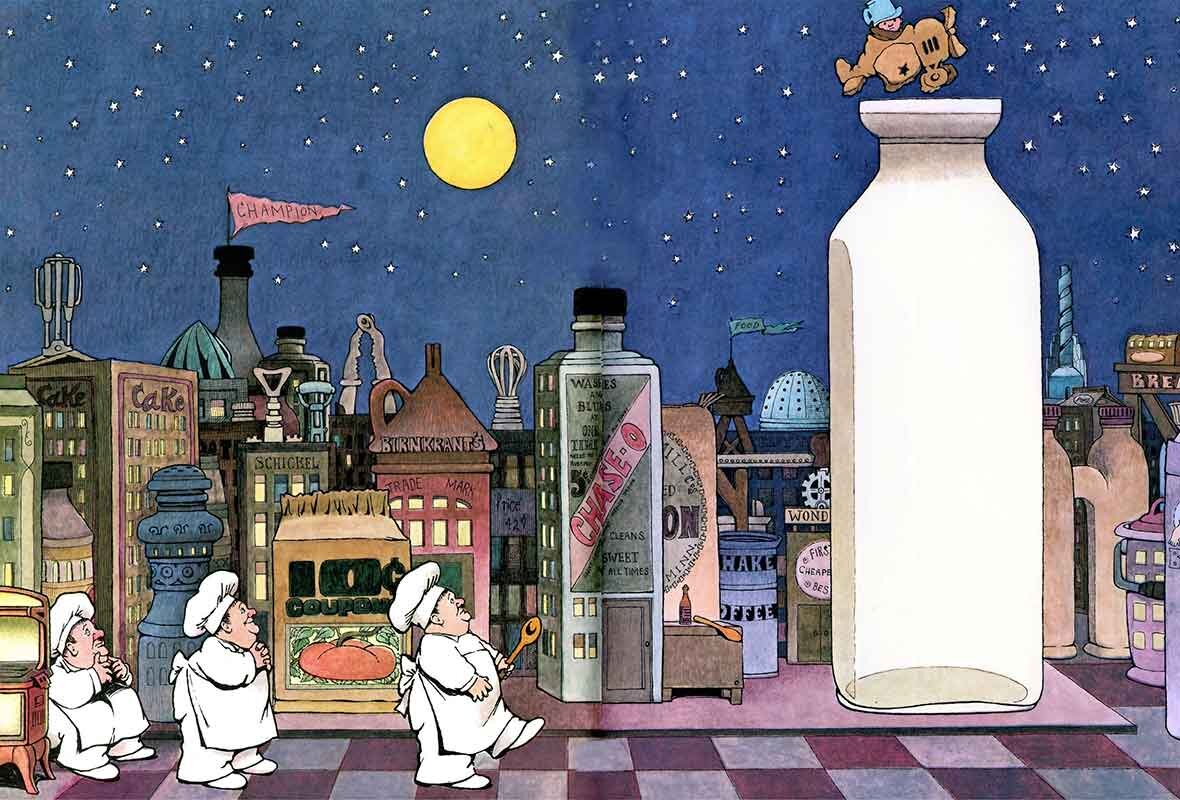

There are few picture books as ubiquitous and iconic as Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are. The images are entrenched in public consciousness: Max’s pointy-eared suit with his whimsical crown, the wild things thrashing about under the light of the moon, the moody greens and purples of the trees. These images tell a captivating story of a child overwhelmed by his own emotion, who sets off to find himself a world all his own, then is able to return home when he is ready. Sendak, who, despite his success in children’s literature, primarily considered himself an illustrator/graphic artist, refused to shy away from difficult themes, which revolutionized the genre of children’s literature. His books dealt with death, discomfort, anger....all emotions children feel, but are often taught to avoid. The captivating illustrations of Where the Wild Things Are are immersive and moody; the heavy cross hatching throughout each drawing creates a fuzzy, dreamlike effect. Sendak’s color choices are a far cry from the primaries and neons chosen by more traditional texts for children; sulfuric greens and dusty pinks catch the reader’s eye without overwhelming them, creating a surreal display of bizarre creatures and strange lands (this is arguably not even Sendak’s most masterful use of color; I would propose that the blue used in the night sky of In The Night Kitchen deserves its own article). Sendak’s monsters are hideous (as they should be- Max’s rollicking energy is not suitable for anything too cutesy), but charming, their mouths open in unabashed grins, suggesting how much they truly enjoy being wild things. As Sonheim mentions, Sendak’s juxtaposition of image and text is masterful; he creates a visual relationship between the two in order to propel the story’s dynamic. The pictures and words crescend and recede; the book starts and ends with a blank page adorned with a single phrase. Scenes like the ‘wild rumpus’ are overwhelmed with illustration, details stretching from one edge of the page to the other, expressing the indescribable emotions that come with howling late into the night. Sendak’s illustrations immerse the reader in the whimsical, the bizarre, even the grotesque; holding nothing back, not the gaping fangs or swirling storms or the endless night sky. Sendak’s artistic mastery is not confined to Where the Wild Things Are, though it is true that he created something completely singular with that story; the creeping sunflowers of Outside Over There and the miniature city of In the Night Kitchen are just as captivating. Sendak’s work deftly explores the darker sides of fantasy and whimsy while empowering children to take risks and indulge what is unconventional within themselves. The illustrations he created for this purpose exemplify the true artistry present in the genre of children’s literature.

A scene from Where the Wild Things Are. Photo courtesy of bustle.com

A scene from Outside Over There. Photo courtesy of medium.com

Scene from In the Night Kitchen. Photo courtesy of leitesculanaria.com

Faith Ringgold (1930-)

Cover of Tar Beach, courtesy of theracetoread.wordpress.com

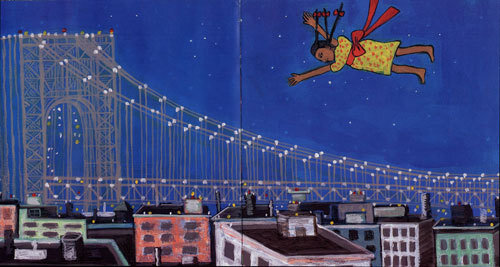

Another artist-turned-children’s book author, Faith Ringgold, is best known for her textile works, and her first children’s book, Tar Beach (1991), is based on a story quilt of the same title. In a 1994 interview, Ringgold claimed that “Tar Beach was not written for children, it's just written for people, but it turns out to be great for children too. It was written to help recall childhood, to help you think back on your childhood (Graulich, Witzling 9).” Indeed, the book was an extension of Ringgold’s experimentation with relationships between image and text. Her story quilts and paintings often contain text, lines upon lines winding around the panels discussing art, femininity, and the black experience. Ringgold’s works serve to uplift the voices of black women, and her children’s books often include African fables and historical black figures in order for black children to see themselves reflected. Tar Beach follows the optimistic protagonist Cassie Lightfoot, who would become a fixture in many of Ringgold’s books. Cassie describes her experience flying away from her tar roof in the summertime, gazing on the city from above and claiming it as her own. Cassie’s flight echoes African-American folktales of people that could fly, and used that flight to escape slavery. High above the earth, Cassie is free from the prejudices that confine her and her family; as she glides through the deep blue sky, the city morphs into her fantasy. Ringgold’s joyful, dreamlike illustrations effectively convey the themes of personal freedom and empowerment through imagination. The black expanse of Cassie’s tar roof, coupled with the cerulean sky, eliminates the boundaries of the page, suggesting that Cassie could fly on forever if she wanted to. The patchwork borders also play with the boundaries of the page, interrupting the form of the book to give way to the tale’s true nature as a story quilt. Ringgold’s use of perspective is fascinating; Cassie resembles a paper doll as she flies through the air with arms outstretched, and the city below her layers up beneath her like it is growing into the sky. The closeups of her building’s roof, however, use a slanted, dramatic perspective, the characters seeming to float above the city as they move across the roof. The illustrations convey the joy and depth Cassie finds in her experience as a young black girl living in the great, glittering city. In Ringgold’s following books, Cassie travels back and forth in time to discover historic figures like Harriet Tubman in Aunt Harriet’s Underground Railroad in the Sky (1992). Ringgold began to identify herself as a children’s author as well as an artist, and created many more vibrant representations of the black experience like Dinner at Aunt Connie’s House (1993), The Invisible Princess (1999), Harlem Renaissance Party (2015). Faith Ringgold’s picture books combine folklore, textiles, painting, and the written word to create a vivid tapestry of black experience in America.

Cassie flying over the George Washington Bridge. Photo courtesy of portfolio.panynj.gov

Jacque Roethler’s article “Reading in Color: Children's Book Illustrations and Identity Formation for Black Children in the United States” describes the importance of black representation in children’s literature in terms of helping black children forge their identities. Since picture books provide children with visual language with which to interpret their world, it is essential that they see themselves within those narratives in order to establish their identities. Roethler asks, “If African American children are absent from the illustrations in almost every picture book they see, how are they to judge their place in this society (Roethler 97)?” The connections forged between children and illustrations are essential for development, therefore it is essential that there is diversity in children’s literature in order to establish connections with children from all backgrounds. Faith Ringgold’s work depicts the nuances of black life with honesty and joy, which has the potential to empower generations of black children as they see their experiences and their potential reflected on the page.

One of the Tar Beach story quilts. Photo courtesy of the VMFA

Shaun Tan (1974-)

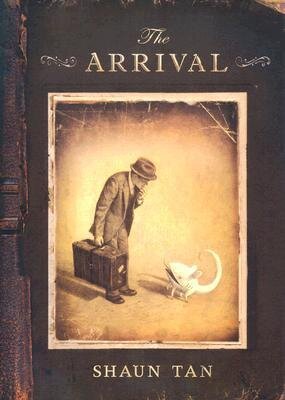

Cover of The Arrival, courtesy of Shaun Tan’s website.

Australian artist Shaun Tan explores the depth of what images can convey in his stunningly detailed fantasy works. Tan’s worlds are rich with creatures and architecture that are entirely unfamiliar yet strangely inviting. Whether he renders his scenes with fine-tuned graphite or thickly layered paint, Tan infuses his works with life and light, tackling the full spectrum of emotions with each contemplative tale. In a brilliantly written lecture for the Australian Society of Authors in Sydney in 2009, Tan discusses his fascination with the relationship between the written word and the image. He mentions the “static” nature of his fine arts background, then contrasts it with the “kinetic” nature of writing. Tan has clearly worked out a way to use image as a kinetic force, as his stories speak for themselves often without a single line of text. In this incisive passage taken from the lecture, Tan seems to invoke the art theory of ‘looking and seeing,’ as he states:

A page from The Arrival, courtesy of Shaun Tan’s website.

In Peggy Albers’ article “Theorizing Visual Representation in Children’s Literature,” she discusses the difference between looking at an image and seeing it at length. Looking at an image, according to art theory established by John Berger, means acquiring information from that image and recording what its characteristics are (Albers 167). Seeing is where the real work takes place; truly seeing is to make a meaningful connection between oneself and the object, or the object and the world. It is clear that Tan employs this philosophy in his works; he encourages the reader to look beyond the kooky animals and squiggly buildings and internalize truths about themselves and their place in the world. Nowhere is the concept of seeing more apparent than in The Arrival (2006), as there is simply so much to take in. This wordless, long-form picture book zooms in to highlight the tiniest detail and zooms out to showcase the largest cityscape. The Arrival tells the story of an immigrant family who travels to a new city after fleeing persecution. Tan effectively symbolizes the acute strangeness of adjusting to a foreign country by immersing the reader in a world beyond recognition. Strange creatures, foods, architecture and language both overwhelm and fascinate the protagonist, a father who must find work in this strange land before his family joins him. Tan’s illustrations spare no detail, particularly when it comes to displaying emotion; the reader can follow the man’s emotional journey on his face as he is frightened, frustrated, and intrigued by his surroundings. The story deftly portrays the connections forged between immigrants, as the unnamed protagonist encounters multiple people who have also fled from their homes to settle in this new world. Themes of grief, war, and camaraderie are evident in both the subtle facial expressions and the sweeping dramatic scenes. There seems to be an endless depth to the pages of The Arrival: readers will find themselves peering into the illustrations, layers of detail stretching back as far as the eye can see. This book is undeniably a work of art, one that poignantly captures the nuances of the immigrant experience without having to say a word. Other books of Tan’s like Rules of Summer (2013) and The Lost Thing (2000) also utilize conscious relationships between word and image: Rules of Summer’s vibrant illustrations are accompanied by pithy ‘rules’ that are broken throughout the book, and The Lost Thing is told through a young boy’s handwriting, his pragmatic account juxtaposed with outlandish illustrations. Tan’s approach to picture books is deliberate and profound; his use of social commentary is effective and poignant, but he also wants the reader to find individual meaning in the work that they can connect to their own lives. He does not describe his works as being meant for children, but their accessibility through vivid visual language is engaging and inspiring to all ages.

Page from The Lost Thing, courtesy of Shaun Tan’s website.

Page from Rules of Summer, courtesy of Shaun Tan’s website.

Conclusion-

The artistic value of children’s books is unique, which is why it is often debated in the art world. The confusion often lies in the myriad of purposes picture books can serve. Children’s books exist as art objects, as literature, as toys, as mementoes, and more… Children’s literature shapes the way children come to perceive the world, thereby shaping how they move through it. Picture books occupy an essential space at the crux of visual learning and burgeoning literacy; their impact on developing children impacts society. When we perceive children’s literature as containing multitudes rather than assigning it to one category or another, then we come to understand the artistic impact these images can have. Whether it was Winnie the Pooh, Clifford the Big Red Dog, Curious George, or another childhood favorite, these characters taught you about art before you even knew what art was, kickstarting your understanding of visual language and giving you tools you will use for the rest of your life.

Sources-

https://www.brainpickings.org/2012/02/24/childrens-picturebooks/

https://www.shauntan.net/

Albers, P. (2008). Theorizing Visual Representation in Children's Literature. Journal of Literacy Research, 40(2), 163-200. doi:10.1080/10862960802411901

Graulich, Melody, and Mara Witzling. "The Freedom to Say What She Pleases: A Conversation with Faith Ringgold." NWSA Journal 6, no. 1 (1994): 1-27. Accessed August 20, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4316306.

Roethler, Jacque. "Reading in Color: Children's Book Illustrations and Identity Formation for Black Children in the United States." African American Review 32, no. 1 (1998): 95-105. Accessed August 20, 2020. doi:10.2307/3042272.

SONHEIM, AMY. "Sendak's Sustainable Art." PMLA 129, no. 1 (2014): 116-18. Accessed August 20, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24769429.

Staff contributor Thea Hurwitz